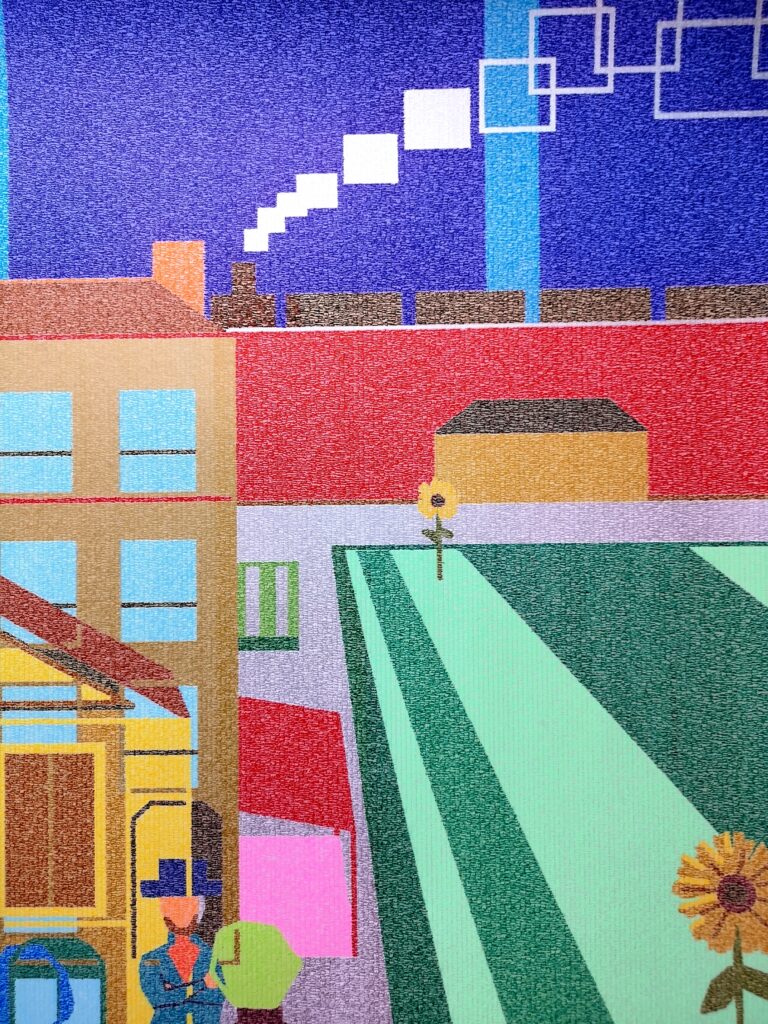

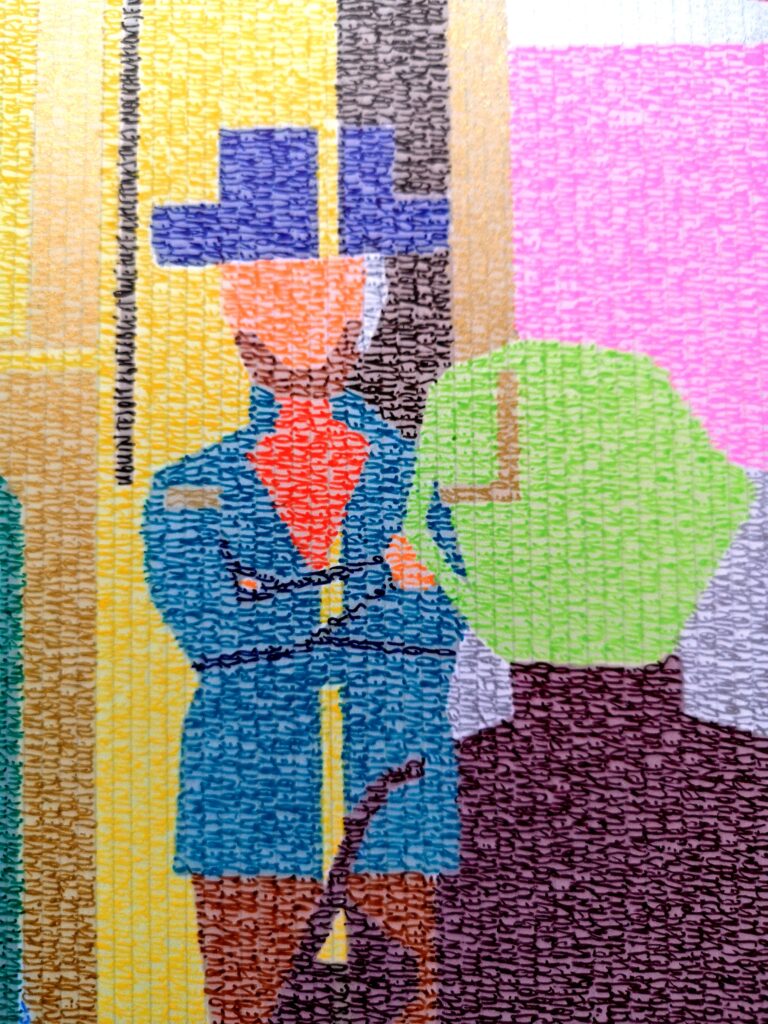

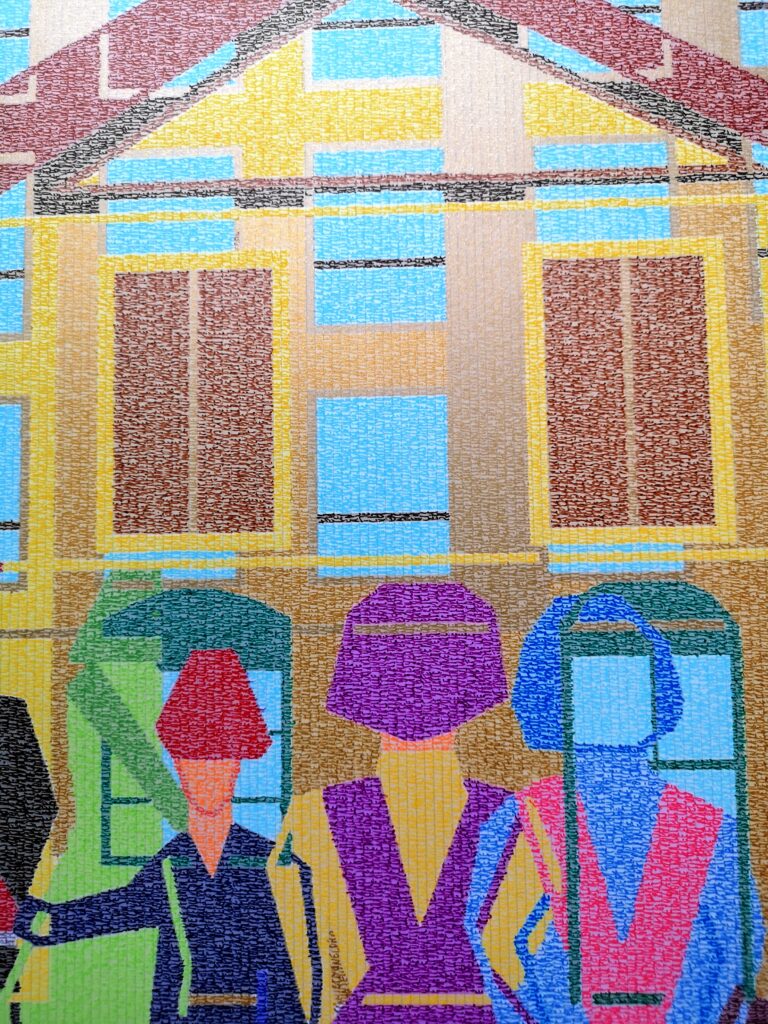

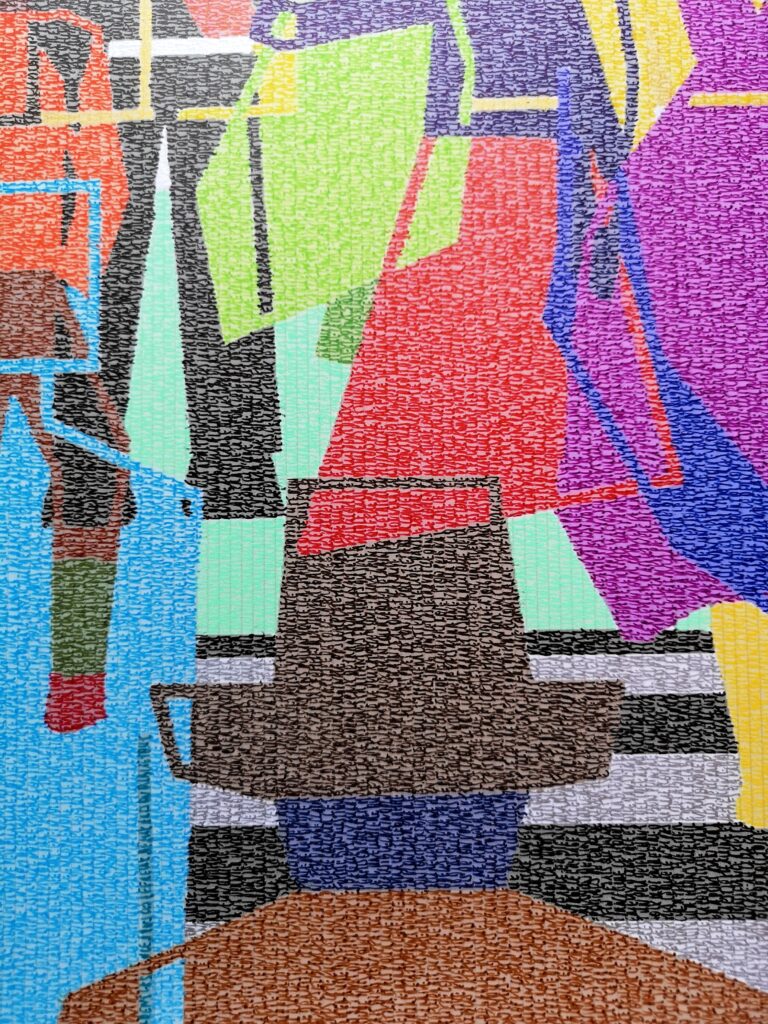

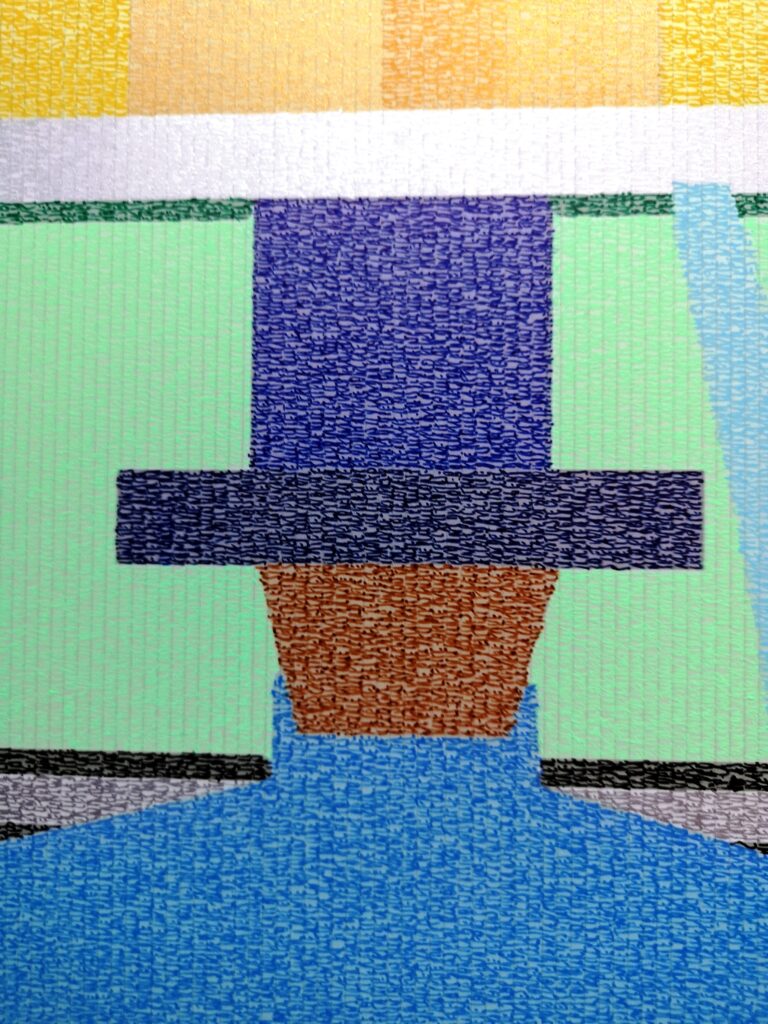

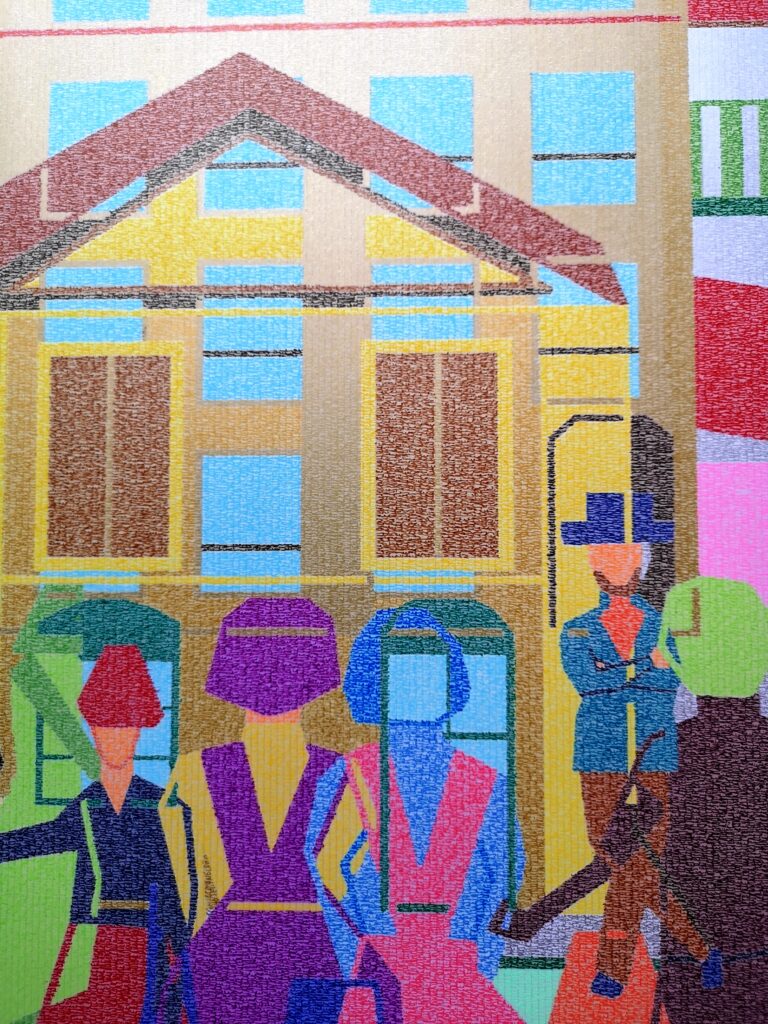

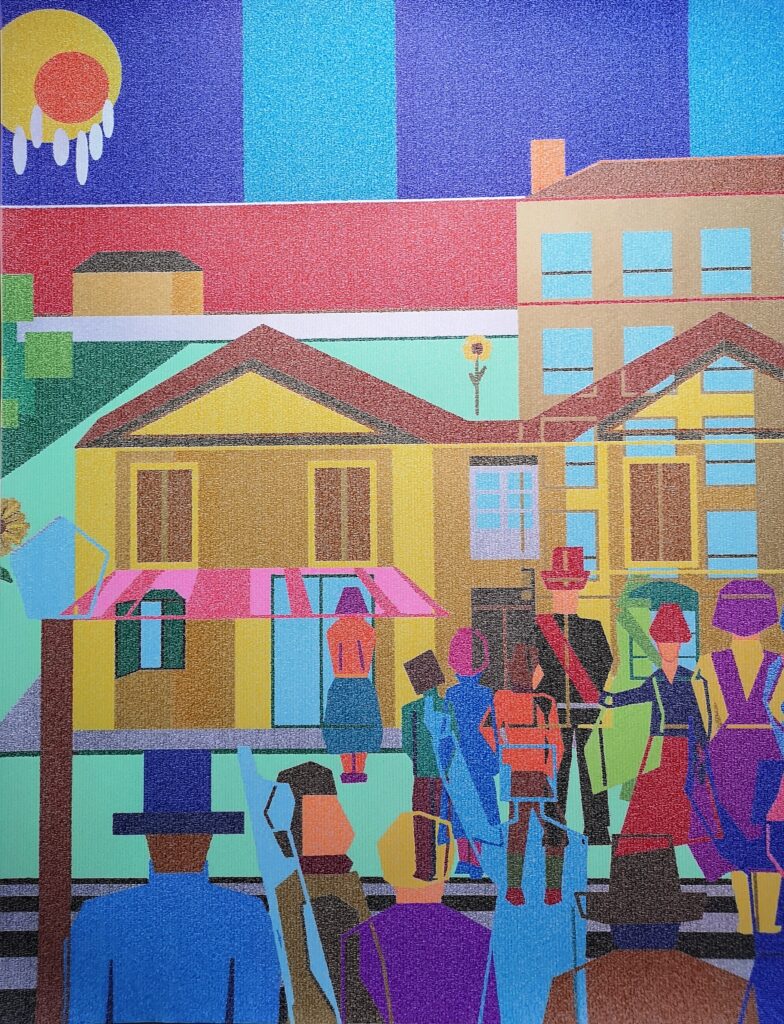

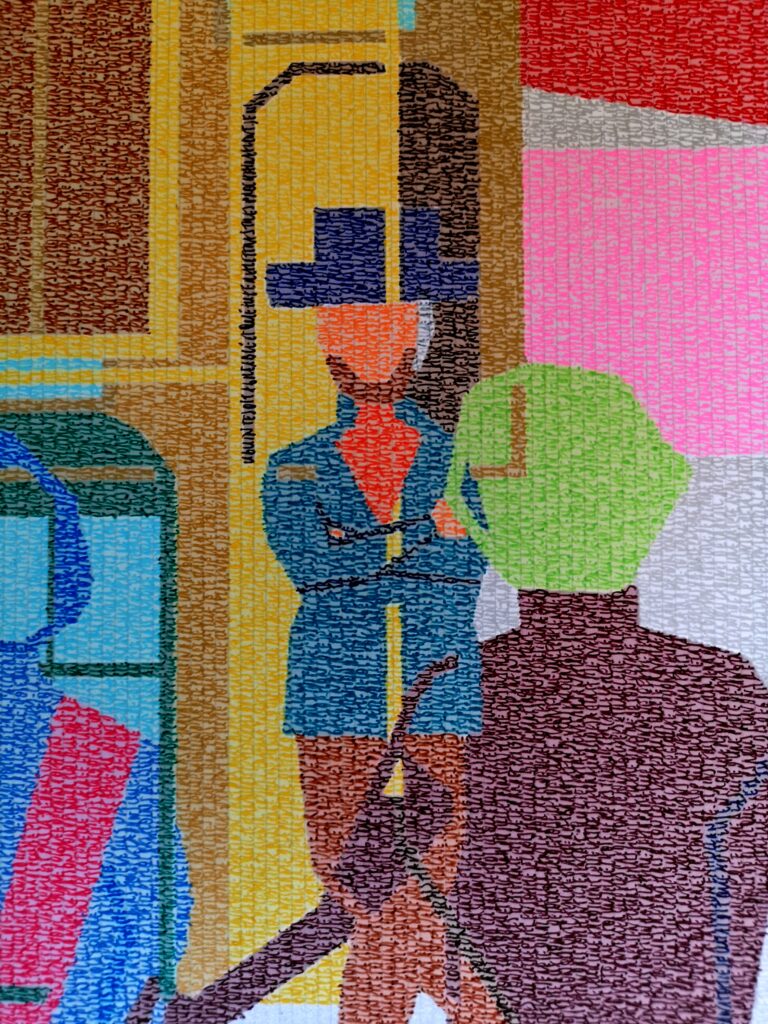

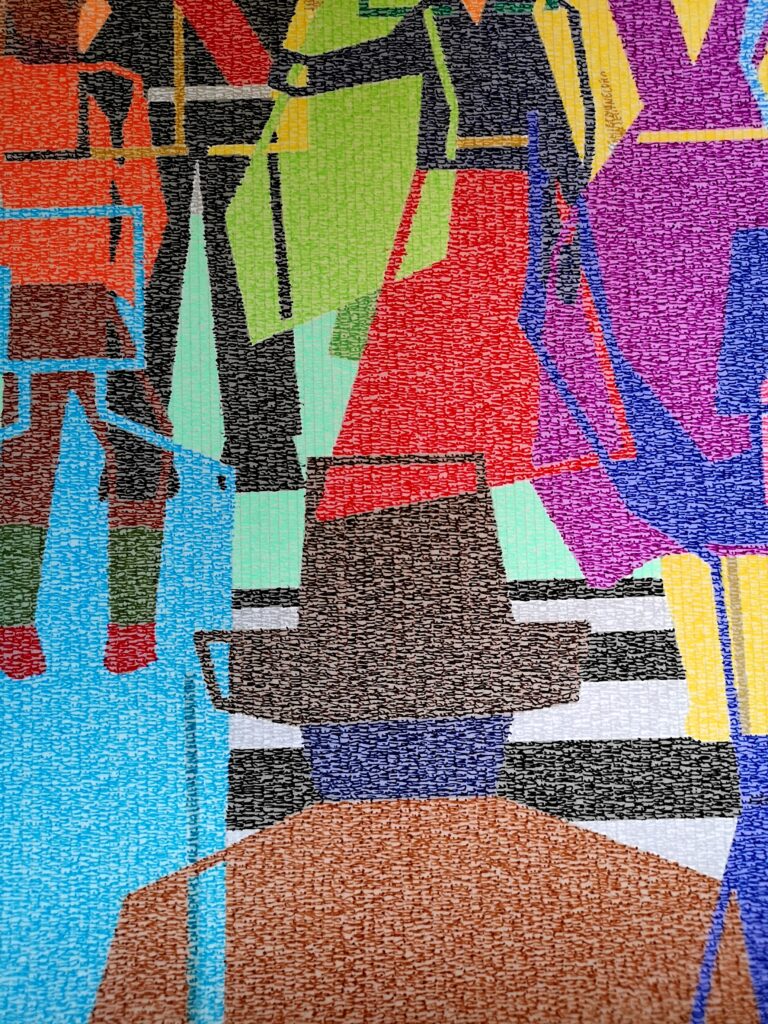

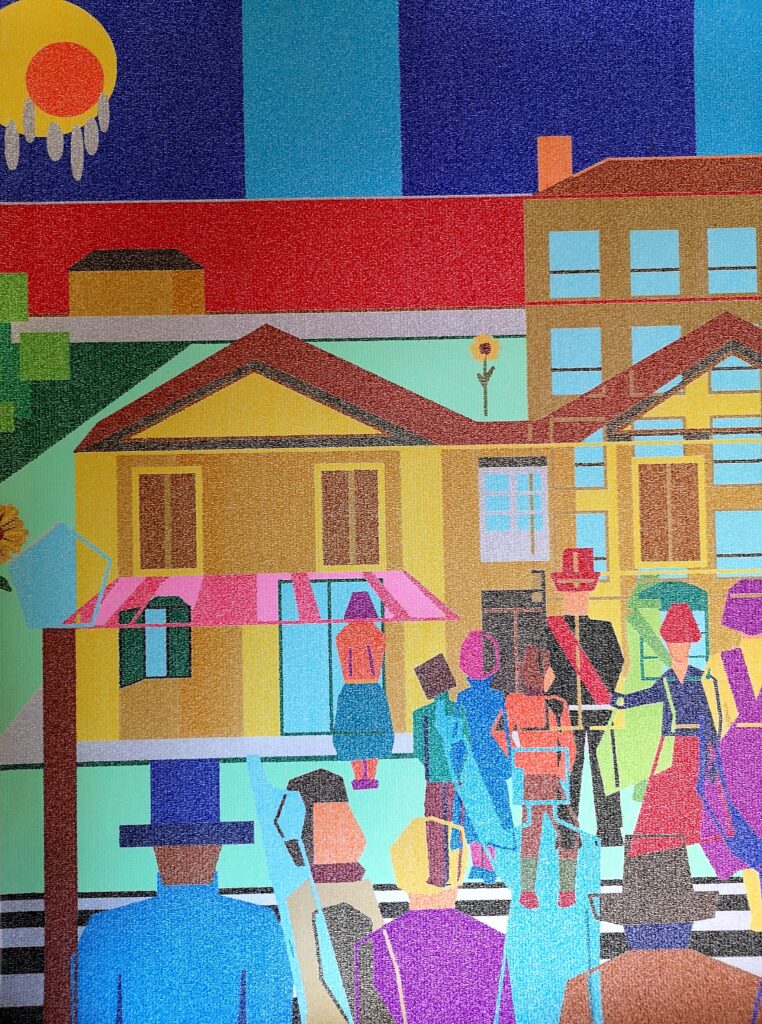

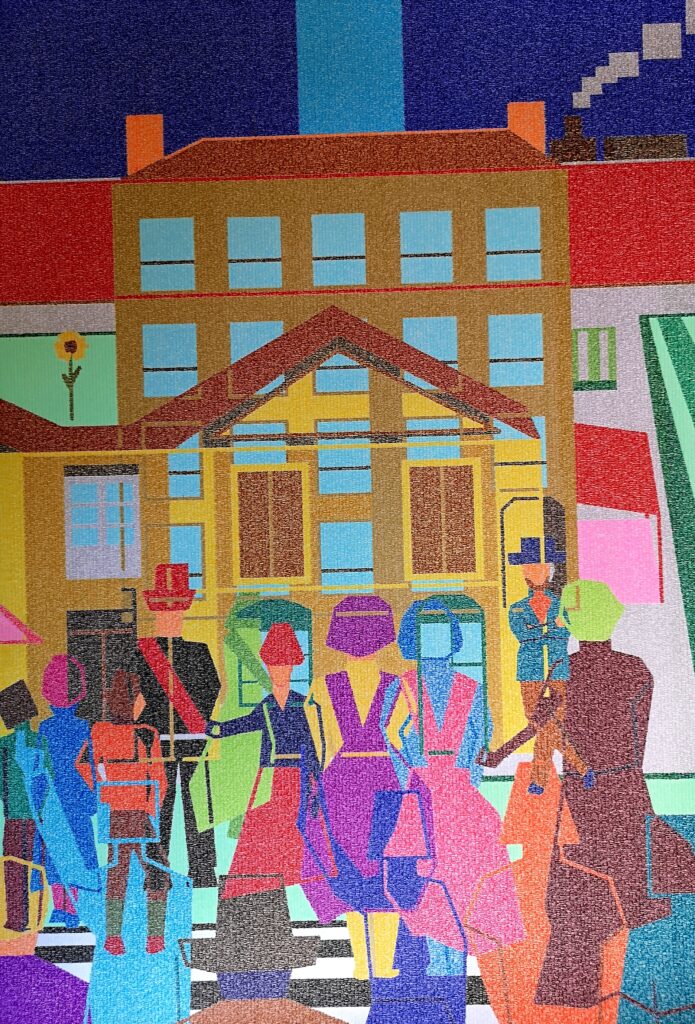

THE PETITION AGAINST VAN GOGH

© Ivan Cangelosi, 2021

106 x 85 cm

Ink on paper

Handwriting of the whole correspondence between Vincent and Theo Van Gogh (Arles period) – French language

The name of Vincent Van Gogh (Zundert, The Netherlands, March 30, 1853 – Auvers sur Oise, France, July 29, 1889) is probably the one that, more than others, is associated with art. His career as a painter, which began as a self-taught at an age no longer very young (he was 27), lasted only 10 years, during which he produced about 900 paintings and more than a thousand drawings (in practice the average of one work every 2 days), ending on the 29th in July 1889, the day he died due to the fatal wound caused by a gunshot, probably self-inflicted.

Van Gogh’s most famous works, those characterized by the exaltation of colors and their abundant application on canvas, date back to the French period of his activity (1886 / 87-1889) and in particular to the period in which he lived in Arles and Saint-Rémy-de-Provence (where he was admitted to a psychiatric hospital) from 1888 to May 1890.

From the beginning, Vincent Van Gogh did not have in Arles an easy life, and not only because of the long-standing economic problems (Van Gogh, having sold only one painting when he was alive, was financed throughout his artistic life by his brother Theo, a wealthy art dealer who lived in Paris, who several times a month sent him money, as well as colors and canvases, which were at that time also very expensive) but also for an instinctive ostracism and ostility shown by the Arlesians towards him, as stated by Vincent himself in one of the countless letters sent to his brother. The distrust of most of the inhabitants of Arles was worsened by the profound sense of loneliness felt, due to the persistent isolation and the lack of social relations. In order to alleviate the suffering of loneliness in his brother, Theo van Gogh managed to convince Paul Gauguin, who was also in great financial difficulties, to join his brother Vincent in Arles, a solution that would have allowed, on the one hand, Vincent to enjoy the company of his admired artist friend and, on the other hand, Paul Gauguin to receive money from Theo Van Gogh who, buying some of Gauguin’s paintings, in exchange for his trip to Arles, had somehow alleviated Paul Gauguin’s financial difficulties.

Unfortunately, the coexistence between the two artists, temperamentally very different from each other, soon turned out to be complicated. The two painters soon began to have differences of opinion on many issues and the altercations often took place in a harsh and, towards the end of their coexistence, even violent way.

It so happened that on the evening of December 23, 1888, after having had an hard discussion with Paul Gauguin, Vincent Van Gogh had a severe nervous breakdown, as a result of which he mutilated his left ear. The episode had even more serious developments due to the fact that Vincent, once he cut off his ear with a razor, put it in a paper wrap, run to the brothel that was not far from his house, and gave it to a prostitute (Ms. Rachel) telling her to jealously keep that object as something precious.

Once back home (the famous “Yellow House” painted by Vincent Van Gogh in one of his paintings), he was found the next day almost lifeless by the police and taken to the hospital.

During his stay at the Hospital, Vincent Van Gogh learned that a number of Arles citizens had joined together to sign a petition against him to be sent to the mayor in order to get him interned or imprisonned. In a letter to his brother Theo, dated March 19, 1889, Vincent writes:

“My dear brother,

I seemed to see so much restrained brotherly anguish in your kind letter that it seems to me to be my duty to break my silence.1 I write to you in full possession of my presence of mind and not like a madman but as the brother you know. Here is the truth: a certain number of people from here have addressed a petition (there were more than 80 signatures on it) to the mayor (I think his name is M. Tardieu) designating me as a man not worthy of living at liberty, or something like that.2

The chief of police or the chief inspector then gave the order to have me locked up once again.3

Anyway, here I am, shut up for long days under lock and key and with warders in the isolation cell, without my culpability being proven or even provable.

It goes without saying that in my heart of hearts I have a lot to say in reply to all that. It goes without saying that I shouldn’t get angry, and that apologizing would seem to me to be accusing myself in such a case.

Only to warn you: to free me – first I don’t ask it, being sure that all of this accusation will be reduced to nothing.

Only I say to you, you would find it difficult to free me. If I didn’t restrain my indignation I would immediately be judged to be a dangerous madman. In waiting let us hope, besides, strong emotions could only aggravate my state.

If in a month’s time, though, you have no direct news of me, then act, but as long as I’m writing to you, wait.

That’s why I now ask you to promise to let them act without getting yourself mixed up in it.

Consider yourself warned that it would perhaps complicate and confuse the matter (…)

So you can imagine how much of a hammer-blow full in the chest it was when I found out that there were so many people here who were cowardly enough to band themselves together against one man, and a sick one at that (…)

I won’t hide from you that I would have preferred to die than to cause and bear so much trouble. What can you say, to suffer without complaining is the only lesson that has to be learned in this life.

How I’d like to be able to send you my canvases, but everything is under lock and key, police and keepers of the insane (…)

More soon, I hope, my dear brother, don’t worry. It’s perhaps a sort of quarantine I’m being put through. What do I know?”